The 38th Space Prize for International Students of Architecture Design

[Fluid Boundaries: Negotiating Internal and External Discourses of Architecture]

SUBJECT

The theme of the 38th Space Prize for International Students of Architecture Design begins from the perspective that architecture is a discursive practice. Michel Foucault viewed discourse as a social structure intertwined with power and knowledge. According to his theory, discourse determines what is accepted as truth and what topics can be discussed within a particular era and society. It encompasses opinions, assumptions, and values about a specific subject, shaped and transformed by social contexts, ultimately forming or reproducing social realities. The system that defines what can and cannot be said about a given subject—discourse—determines what we regard as 'truth' and compels us to think and act in particular ways.

However, in contemporary architecture, there is no singular discourse that dictates a specific way of thinking and acting. It seems that only highly fragmented and individualized discourses exist, which no longer function as social power. The last period when a specific form of architecture was regarded as truth, and when clear discursive structures shaped both architectural practice and education, was likely the Beaux-Arts era. According to Hyungmin Pai, “The Beaux-Arts system was the last example of maintaining widely shared conventions as architectural discipline.”1 During this period, the boundaries of architectural discourse were relatively clear, rooted in Western classical architecture derived from ancient Greece and Rome. There was a well-defined process of training required to become an architect, as well as a clear scope of professional duties and roles that architects were expected to fulfill after their formal recognition.

In contrast, the boundaries of contemporary architectural discourse have long become blurred. This is likely due to the gradual erosion of architectural discourse by external influences over time. In modern architecture, elements of architecture and non-architecture coexist in a hybrid form. At some point, architects were expected to become heroes reviving decaying cities, pseudo-scientists offering plausible solutions to global climate crises, and activists restoring fractured communities. More recently, architecture appears to be burdened by a compulsive need to compete with artificial intelligence, serving as proof of humanity’s unique artistic creativity.

Architecture, which once existed within clear discursive boundaries, can no longer stand alone; it is increasingly influenced by external demands and forces that were once beyond its internal domain. As social relationships grow more complex and technological advancements accelerate, architecture seems to be drawn into addressing increasingly complicated problems that it cannot solve on its own. It appears that architecture is now required to engage with issues beyond its traditional scope, despite the fact that these issues cannot be fully resolved through architecture alone.

The proposition that architecture is a discursive practice, in the modern sense, implies that the role, definition, function, and perception of architecture are in an extremely fluid state, mediated by its dynamic relationship with specific external discourses. From the perspective of these evolving discursive relationships, architecture may increasingly find itself in a passive position.

Paradoxically, this condition leaves architects with the critical task of deciding what should serve as the material for discourse. In a situation where no dominant discourse exists, assigning value becomes part of the architect’s responsibility. What should be done, or what should be avoided? The idea that architecture is a discursive practice inherently involves an active stance—choosing what is worth engaging with or must be engaged with, and excluding what should not be.

The 38th Space Prize for International Students of Architecture Design is founded on the premise that internal and external discourses of architecture interact with each other. Its goal is to encourage participants to develop their own discourse and, through this process, discover new possibilities in architecture. Entries will be evaluated based on several key criteria outlined below.

1. What will the architect choose as the central discourse?

Participants are encouraged to select one issue from a wide range of contemporary concerns—climate crisis, energy, war, community, regionality or historicity, development vs. preservation, artificial intelligence, or other pressing problems of modern life—and argue for the necessity of their choice. What is critical in this process is how participants independently identify and select what should become the central discourse of architecture, and the persuasiveness of their justification.

2. Fluid boundaries of discourse: Understanding the internal and external of architecture

The chosen central discourse must be explained in the context of fluid discursive boundaries. Participants are expected to explore and define what constitutes the interior and exterior of architecture. From the perspective of the Anthropocene, the history of architecture and architects may seem fleeting, but within that brief span, there have been significant shifts in the boundaries of discourse. Participants are encouraged to examine how these boundaries have evolved over time.

An architect, much like a medieval stonemason, may possess unique, irreplaceable skills passed down through generations, yet they may also be seen as powerless without input from various specialized consultants. This inherent incompleteness of the architectural profession creates a dynamic relationship between internal and external discourses. By contemplating this blurred boundary, participants may find opportunities to redefine or expand the role of architecture and architects. (It is equally valid to argue that architecture cannot solve specific social issues.)

3. Architecture in real-world social relations

Participants should critically interpret the reality in which architecture exists. The proposal should demonstrate a clear understanding of architecture’s role within the complex social, cultural, economic, and existential relationships that shape real life—avoiding baseless abstractions or overly romantic approaches. Rather than speculating about an unpredictable future or virtual space, participants should select a tangible, real-world site for their project.

footnote 1. The portfolio and the diagram, by Hyungmin Pai, The MIT Press, 2006

General Review

The 2025 SPACE International Student Architecture Awards invited participants to explore the ever-expanding boundaries of architecture, acknowledging that the discipline’s social roles and professional functions are in constant flux. The competition sought not only hypotheses and experiments envisioning the future of architectural practice but also reflections on its unchanging past—an attempt to understand architecture through the complex interplay of history, theory, tradition, material, and technology.

This theme stems from an acute awareness that autonomous architectural discourse is fading, its boundaries steadily eroded. Paradoxically, while this sense of crisis is universal, valid responses are inevitably individual. Since time and place always shape architecture differently, there can be no generic or universal solution. Even amid shared crises, the personal and particular must be continually reinforced, for it is precisely these that nurture the soil of discourse.

The submitted works, though diverse in approach, share a common pursuit: to probe the “boundaries of architecture” while earnestly reflecting on the social, ecological, and institutional responsibilities that architecture must assume today. They reveal a collective awareness of an era in transition, seeking an architecture that operates between society, ecology, technology, and systems of governance. Although the density of inquiry and depth of thought vary across projects, each attempts to critically interpret the inescapable condition of architecture—its entanglement with time and place. None are complete, yet each holds the potential to become a seed of critical thought, inspiring future discourse.

GRAND PRIZE

LIM, SE BIN

OH, HYE RIN

KO, SEO YEON

INHA UNIVERSITY

De-Construction To Re-Define

Architectural Attitude Toward Spaces That Have Fallen After Their Era: Designing Disappearance as a New Mode of Existence

Architectural Attitude Toward Spaces That Have Fallen After Their Era: Designing Disappearance as a New Mode of Existence

Architects have long engaged in translating complex social demands into built spaces. Yet in today’s rapidly shifting society—marked by population decline, metropolitan concentration, and industrial transformation—obsolete and abandoned spaces are proliferating across both cities and regions. Architects are thus required not only to create new spaces, but also to reinterpret and transform those that have fallen into disuse.

At this turning point, the question is no longer “how to create space” but “how to meaningfully conclude and transition spaces that have outlived their era.” Rather than simple demolition, the architect’s task is to guide spaces to exit gracefully, integrate into new orders, or return to nature– not simply demolishing them.

The Jangseong Mining Complex in Taebaek, Gangwon Province, once the heart of coal mining and a pillar of Korea’s industrialization, was abandoned after the industry’s decline. What remains are scars of excavation, heaps of waste stone, and polluted soil, while the region struggles with depopulation and economic stagnation.

We propose to redefine this site as a place of memory through ecological recovery and return to nature. The primary source of ongoing destruction—tons of heavy-metal-contaminated waste stones—can paradoxically be transformed into zeolite, a material with strong absorption and filtration capacity. By shifting from agent of destruction to tool of restoration, it enables the site’s healing to be architecturally visualized through zeolite based gabion walls. Purified water will flow into the miners’ former bathhouse, reimagined as an exhibition space reflecting the present, and extend to a constructed wetland that restores ecological balance to the land.

The heart of an industry that sustained an era and the source of its resources—some parts dismantled, others fading with time, guided to be absorbed into nature—this is the 'method of disappearance' we propose through this project.

General Review

This project expands the role of the architect beyond the simple act of “building” space, posing instead the question of how to meaningfully bring a space to its end once it has fulfilled its historical role. In doing so, it aligns closely with the competition brief’s call to test architectural choices and their necessity along the boundary between internal and external discourses.

The chosen site, the Jangseong Mining Complex in Taebaek, stands as both a symbol of the industrial era and a ruin left in its decline. The entrant reframes this site not as an object of demolition but as an architectural device mediating memory and recovery. In particular, the proposal to transform mining residues—turning traces of destruction into instruments of renewal—persuasively reconfigures social and ecological discourse through the language of architecture. By converting waste rock into zeolite and employing it as filtration gabion walls, the project creates a purified watercourse that flows into baths, exhibition spaces, and wetlands, clearly demonstrating how architecture can act as a medium for ecological restoration.

Through the paradoxical notion of “designing disappearance,” the project explores the architect’s renewed social role and insightfully captures “decay and recovery” as essential materials of architectural discourse. By confronting the irony that architecture must continue to exist as a built result even “after disappearance,” it generates compelling questions and possibilities for architecture in the face of global crises such as depopulation and climate change—such as, “How might we design the disappearance of parts of Seoul once its population has halved?”

PRIZE OF EXCELLENCE

BAEK, SEUNG JAE

SHIN, SUNG HYUN

INHA UNIVERSITY

시간의 축을 세우다

Is architecture for the present, for the future, or does it belong to the past? Today, architecture no longer remains confined within a single discursive boundary; even the notion of such a boundary has become extremely fluid. Amid this uncertainty, we are compelled to return to a fundamental question: What, then, is the immutable essence of architecture?

Is architecture for the present, for the future, or does it belong to the past? Today, architecture no longer remains confined within a single discursive boundary; even the notion of such a boundary has become extremely fluid. Amid this uncertainty, we are compelled to return to a fundamental question: What, then, is the immutable essence of architecture?

Unlike other objects or technologies, space derives its intrinsic value from its “emptiness.” This emptiness allows space to serve as a vessel that contains the lived time of its users, while the architect interprets the latent possibilities of such space into concrete “programs.” In this sense, temporality constitutes the very essence of architecture and its irreplaceable professional domain. The architect, as a “four-dimensional being” who erects an axis of time within three-dimensional space, must be able to analyze the dynamics among constituent elements and propose programmatic scenarios for whose “time” the space will embrace, responding to the ever-changing demands and challenges of society. Thus, we recognize architecture as a device that links multiple generations and communities through the medium of time, and we approach the contemporary issue of artificial intelligence through an architectural lens.

What role, then, should architecture play in the coming age of artificial intelligence? We note that AI, by producing future information from the accumulation and learning of past data, resonates deeply with the essence of architecture as “temporality.” To us, AI functions both as a programmatic connector that enables interactions across time among members of society, and as a collaborator that extends architecture’s role in addressing present social issues into the future.

Mullae-dong, situated at the crossroads of deteriorating work environments, fading local identity, and generational transition, provided an ideal ground for experimenting with this complex interplay between architecture and artificial intelligence. Here, we sought not only to resolve the current spatial limitations but also to envision, through “Craftsman AI,” a mode of transmission in which the technical knowledge of Mullae’s craftsmen is passed on to artists, ensuring that the unique “Mullae-ness” of place is inherited by future generations. As architects of the future, we propose a design that stands at the intersection of inheritance and innovation-preparing the warmest possible future through the coldest of materials.

General Review

The project Constructing the Axis of Time views architecture not merely as a physical construct but as a temporal apparatus that connects generations and society, posing a philosophical question about the essence of architecture amid rapidly evolving technological environments. Most notably, its interpretation of artificial intelligence—currently the most transformative force reshaping architectural production—as a tool mediating time is both timely and insightful. By designing a system through which past techniques are transmitted to future generations via AI, the work effectively embodies the competition’s theme of interaction between internal and external discourses in architecture. The choice of Mullae-dong as the site further strengthens its realism, demonstrating a thoughtful engagement with the role architecture can play within existing social relations.

However, the work’s exploration of architecture’s “temporality” could have been developed more concretely, particularly regarding how the proposed “artisan AI” might actively generate tangible changes in spatial production. In the current proposal, AI functions more as a metaphor—collecting data from the past and conveying it to the future—while the architectural centerpiece, a tower, remains a somewhat conventional hybrid of local data center and office space.

Questions thus remain: Why is temporality crucial to architecture? Is the architect’s role here to program the ‘artisan AI’? What aspects of Mullae-dong’s temporality are worth preserving and transmitting to the future? Despite these open questions, the project is a meaningful and intellectually grounded attempt to redefine the architect’s professional and discursive position in the age of artificial intelligence.

SPECIAL PRIZE

KIM, DONG JUN

KIM, YEON HEE

PUKYONG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY

비인간종을 위한 입주지원 특별법

In the process of becoming highly organized for human convenience, the modern city has erased the habitats of its original non-human residents. The ecosystem destruction brought about by urban expansion is now an unavoidable problem, demanding a new social and urban role for architecture.

In the process of becoming highly organized for human convenience, the modern city has erased the habitats of its original non-human residents. The ecosystem destruction brought about by urban expansion is now an unavoidable problem, demanding a new social and urban role for architecture.

This project includes non-human species in its urban planning. To this end, we propose the "Special Act on Move-in Support for Non-human Species," a legal and spatial framework that utilizes the planned site for the undergrounding of Seoul's surface railways by 2040 to provide a minimal habitat foundation, allowing non-human species to settle in the city on their own.

We have categorized the space into three types based on its character. The "Type 1 Non-human Residential Area" serves as a safe home, the "Type 2 Non-human Residential Area" as a path connecting these homes, and the "Type 3 Non-human Residential Area" as a zone of coexistence where humans and non-humans meet. The organic connection of these homes, paths, and yards completes the entire city as one giant ecological network.

However, rather than completing the habitat creation in a short period, we induce the ecosystem to stabilize on its own through a gradual and long-term process that includes an ecosystem stabilization period of at least five years, during which human intervention is prohibited. This process, flowing through time from stage 1 (prioritizing the establishment of pollinators), to stage 2 (expansion and protection of non-human species), and finally to stage 3 (coexistence with humans), aims to respect the time required not only for the ecosystem but also for human society to adapt to this new relationship.

This project is a concrete proposal that suggests the new role of contemporary architecture is to support and mediate the process of a new relationship where humans and non-humans coexist, using law, space, and time as its tools. We hope that experimenting with the possibilities of coexistence and supporting the process of recovery under current conditions will become the new role of architecture for living with the city.

General Review

The project Special Act for Non-Human Residency Support is one of the most direct yet conceptually expansive responses to the 2025 SPACE Student Architecture Award’s theme, “Fluid Boundaries of Architecture.” It seeks to liberate architectural discourse from the anthropocentric paradigm and expand the notion of urban agency to include non-human life forms. This approach stands as an outstanding example of translating the brief’s call for the “interaction between architecture’s internal and external discourses”—particularly across social, ecological, and institutional dimensions—into a concrete architectural proposal.

By adopting the framework of a “special act,” the project extends architecture beyond physical outcomes, positioning it as an institutional and social medium. This effectively embodies the competition’s central inquiry into “architectural choice and necessity.” The redefinition of residential zones to include both human and non-human habitats, together with the establishment of a three-phase ecological transition process integrating law, space, and time, demonstrates both discursive depth and logical coherence. Particularly, the project’s understanding of urban ecological restoration not as a short-term installation but as “reconstruction through time” reflects a compelling Anthropocene perspective.

Through the exercise of “legal imagination,” the project reminds us that architecture can continually redefine its social role, shifting its agency toward the intersection of institutional and ecological systems.

JO, YU RAN

KIM, SUN YUP

HONGIK UNIVERSITY

Post_Cultivation Protocol

Rural depopulation idles fields; monoculture/agrochemicals acidify soils. Architecture as discursive practice selects what to keep/connect/operate—here, soil.

Rural depopulation idles fields; monoculture/agrochemicals acidify soils. Architecture as discursive practice selects what to keep/connect/operate—here, soil.

We convert oyster-shell waste into weathering blocks; rain releases CaCO₃. Blocks on decks/railings provide low-dose, long-duration input. Architecture works as operable protocol—shell→soil—via layout/rate/metrics.

Minimal retrofit: remove weak; reuse viable for stay/production/research. Paths use “Seeds—Branching—Avoid—Loop” to spread influence and allow passage/rewilding.

Industrial logic links coastal shells to rural block production; we monitor pH, infiltration, species richness. Operations: residents + municipality; tourism adds small, durable jobs. Build small, shift ecology and at-risk rural industry; transferable.

General Review

The project redefines architecture not as an object but as a protocol—an operational mechanism mediating social and ecological transformation. By converting oyster shells, a local byproduct, into a material for soil restoration, the proposal establishes a connection between coastal industries and rural ecologies. This approach operates with remarkable precision at the intersection of architecture’s internal and external discourses—nature, industry, and society. The clear narrative of “shell → soil” presents architecture as a process of material transformation, posing a fundamental question: not “What should we build?” but “How should it operate?”

By addressing both the specific locality of Eumhyeon-ri, Cheongra-myeon, and the reality of regional extinction, the project articulates a clear rationale for its discursive choices. Its focus on systems, cycles, and local operational structures—rather than on physical form—exemplifies an expanded role for architecture along fluid boundaries. While the spatial experience may remain somewhat linear and underdeveloped, the project is significant in proposing a tangible model for socio-ecological transition. Ultimately, it conveys a powerful message—“small architectures that change systems”—and presents a compelling vision of the ethical and discursive stance that architecture can take today.

LEE, JOO HYUN

KOOKMIN UNIVERSITY

비워둔 집

This project proposes a prototype for a memorial space suitable for death in Korea.

This project proposes a prototype for a memorial space suitable for death in Korea.

In recent times, cremation has become widespread in Korea, and the architectural form of the ‘columbarium’—introduced involuntarily—has become popular. However, Korea has traditionally materialized the spirit, storing and commemorating it in private spaces, while burying the physical body intact. Furthermore, in Korean commemoration, the space for honoring the spirit and its surrounding environment were inherently crucial. There, we remembered the deceased through unfocused vision and skin. Today, columbaria—which came about by chance—fail to properly understand Korea's death culture. Instead, they provoke NIMBYism, creating a vicious cycle in death culture. Moreover, modern urbanization has increased single-person households and nuclear families, while funeral practices have diversified beyond traditional ritual, leading even existing enshrined remains to be neglected. In this situation, what role should future spaces for death be?

The essence of memorializing the deceased in Korea lies in the fulfillment(實) of the living's environment. To achieve this fulfillment, one must empty(虛). Therefore, we aim to eliminate the program for storing remains and its byproduct, the thick ㄷ-shaped wall, leaving only the foundation and roof to bring in the surrounding natural environment. The site selected for this project is the Second Square of Yongsan Family Park, adjacent to the National Museum of Korea. The program reinterprets, within a contemporary context, the burial ground(‘jangji’) where interments once occurred, the ‘temporary mourning hut (‘yeomak’) where the

General Review

The project The House Left Empty critically reflects on the distorted funeral culture and architectural typologies that emerged during Korea’s modernization, addressing death—a subject both universal and long avoided. Beginning with a critique of the institutionalized typology of the columbarium, the project proposes a spatial attitude that realizes “filling through emptiness,” demonstrating an intention to treat socio-cultural spatial forms as essential elements of architecture itself.

Reinterpreting the traditional funerary structures of the yeomak (mourning hut) and jangji (burial site) in a contemporary context, the project elevates the “relational modes surrounding death” above physical form as the true essence of architecture. By removing thick walls and leaving only the podium and roof, it blurs the boundaries between life and death, interior and exterior. Situated within the urban context of Yongsan Family Park, this gesture becomes a profound social proposal—to reintroduce spaces of death into the realm of everyday life.

By reopening the discourse on death through architecture, the project reinterprets and renews the spirit of Korean architecture—the “space that is filled through emptiness”—in a contemporary and deeply resonant manner.

SELECTED WORKS

JUNG, HYEON SEON

KIM, SE YEON

LEE, GUN HEE

SAMYUK UNIVERSITY

Who is Architect?

NAM, SEO JIN

JEONG, IN JUN

AN, GI SEONG

PUKYONG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY

건축이 다시 ( )로서 기능할 수 있을까?

LEE, SI AM

CHANG, YI SO

GONGJU NATIONAL UNIVERSITY

Dealing with Green Field

PARK, SO HEE

JANG, HA RIN

KIM, MIN CHAE

HANYANG UNIVERSITY

시장상가( )아파트

PARK, JEONG IN

KIM, YOON SEO

HONGIK UNIVERSITY

Form of Impermanence

HONORABLE MENTION

MOON, CHAN

KOOKMIN UNIVERSITY

Shelter is Not Enough

KIM, DONG HUI

KIM, DONG RYEONG

KO, JUN HO

JEJU NATIONAL UNIVERSITY

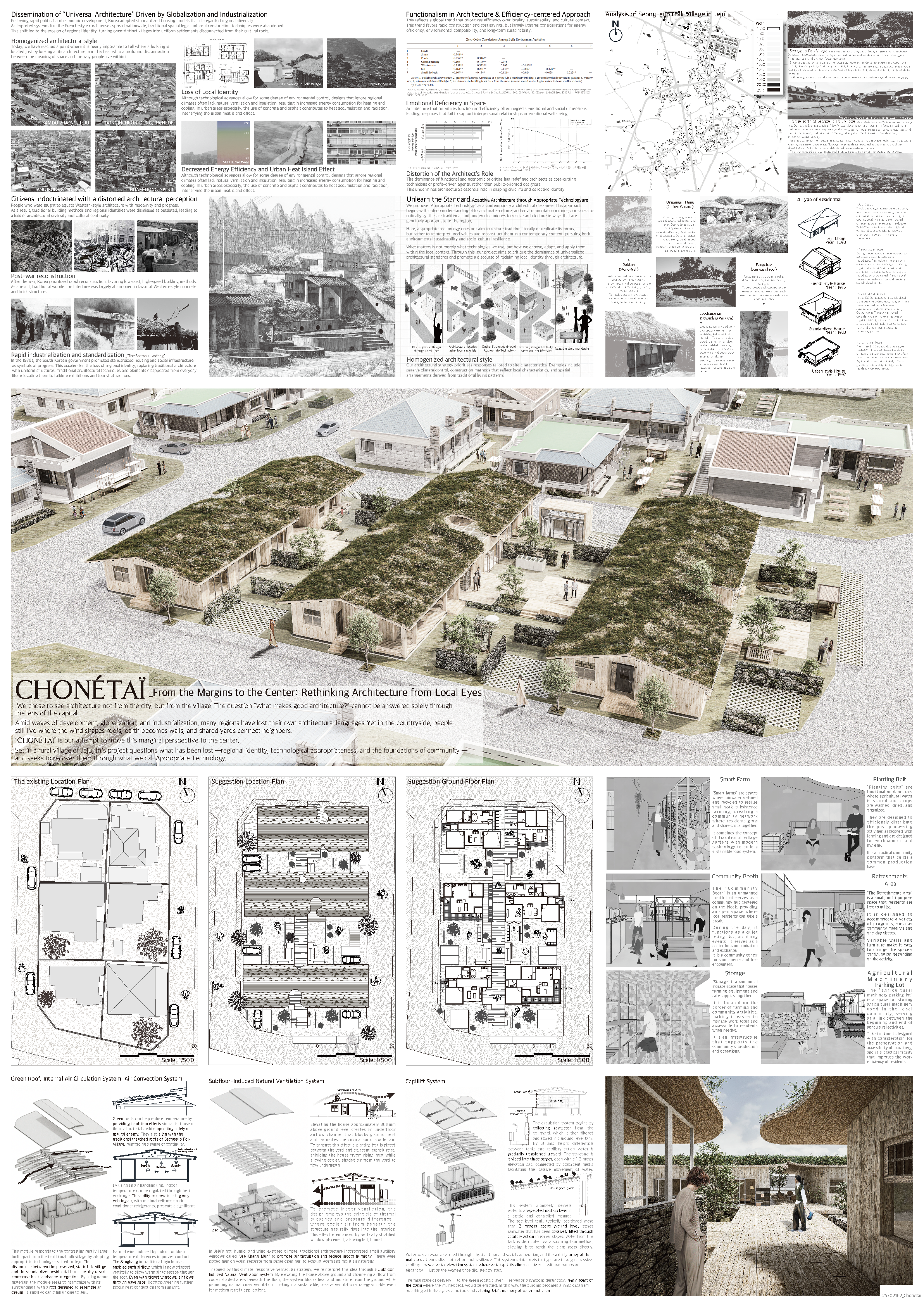

Chonetai

WOO, JI SUN

SEJONG UNIVERSITY

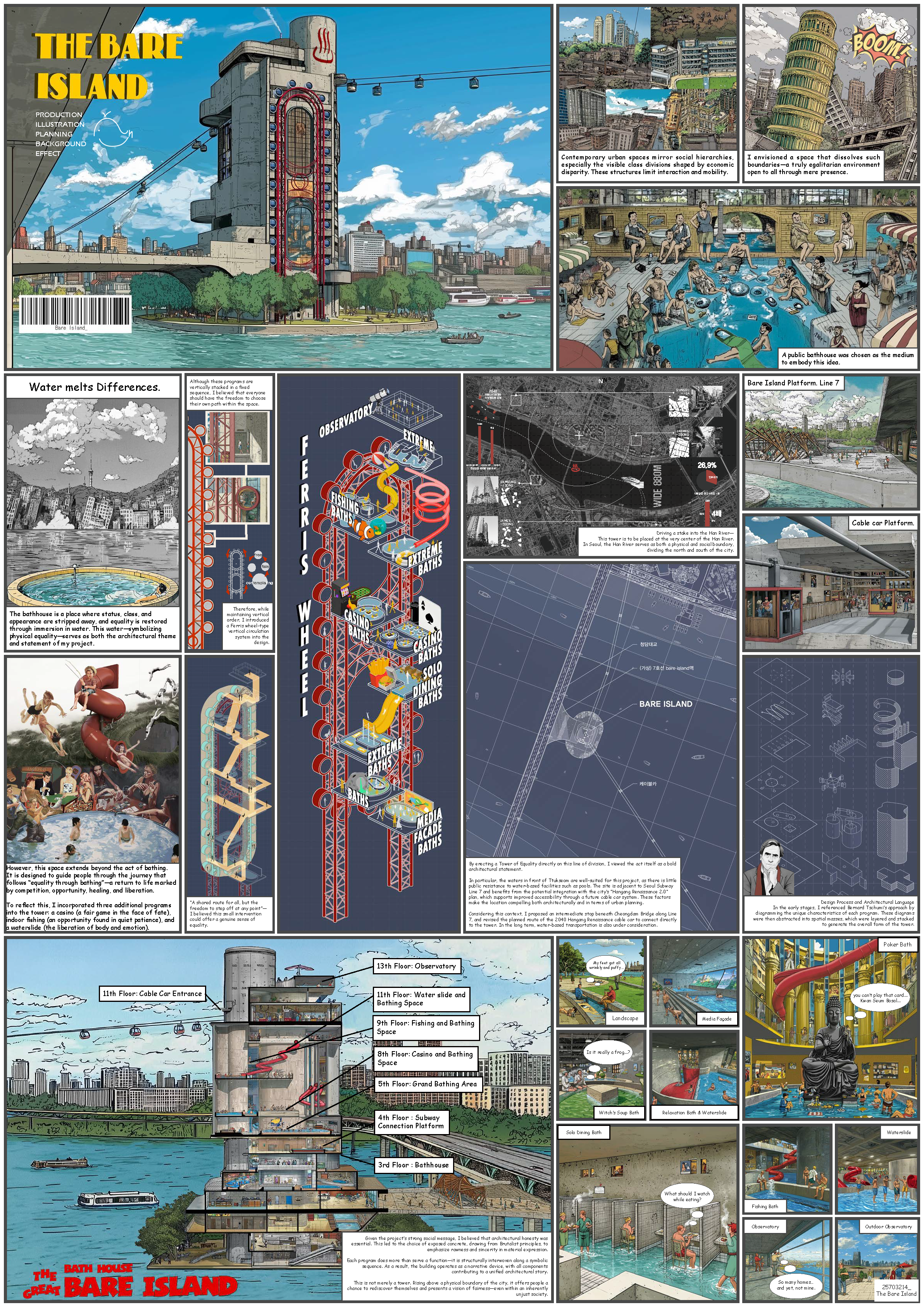

The Bare Island

KIM, JAE HYUN

UNIVERSITY OF ULSAN

Over the Edge