The 28th Space Prize for International Students of Architecture Design

- Investigation of small shelters -

SUBJECT

Investigation of small shelters

Program _ Sustainable ways of building, living, dismantling

At the Space Prize for International Students of Architectural Design, an annual competition that helps explore the realm of architecture, thus expanding the magazine’s scope by allowing young architects to compete under a single theme, the jury wrapped up this year’s program via the final open deliberation on October 26th and announced the winners for 2010. This year’s senior juror, Cho Byoung-soo (Principal of Byoungsoo Cho Architects), challenged the competitors with the specific task of coming up with a method for realizing sustainable building, living and dismantling, under the theme “Investigation Small Shelters.” “I don’t believe in a single, absolute idea in architecture. I believe in profound consideration and the process in which that ‘consideration’ is put to work,” said Cho about the 2010 competition. His remarks aptly describe the characteristics and orientation of the event. Rather than stressing some esoteric ideas or big discourse about architectural theory, he tried to find a value in actual “making,” or the implementation, of architecture for this year’s competition.

A total of 735 students entered the program which increased the total number of winners this year, picking 20 teams in total. Of that group, 10 teams finally made it to the final round. The finalists -nine local teams and one overseas team-were instructed to put forth an extension of the 1st-round challenge, upon which the final open deliberation was carried out.

Upon completing the October 26th deliberation, Cho said he saw ingenious ideas in the students’ works and learned from them, marveling at some incredible details and realistic approaches that were really advanced for student architects. Also, he wholeheartedly praised all the participating architects who had given their 100% during the competition. “In architecture, the difference between actually doing something and just thinking is huge,” said the senior juror. “And only by doing, you discover a new world and experience what is essential in architecture. That’s really important.”

Winning entries for the 28th Space Prize for International Students of Architectural Design were displayed at the Gallery Space (Space Group Building) until November 9th following the awards ceremony held on the 3rd. The exhibition continues online at the Space website. Viewers will find the passionate works of the aspiring young architects, who have poured their heart and soul into the program over the past year.

JURY REPORT

Cho Byoung-soo

Byoungsoo Cho Architects

I found the 10 teams that made it to the final round refreshing, passionate and inspiring. The majority of the teams were able to read not only the physical context of the plot, but also its social-cultural and even historical context, using their keen insight. Sure enough, all 10 of the finalists (teams) exhibited a deep understanding and creative interpretation of the given task, which I found extremely satisfying. They even proposed building approaches that varied widely in materials and techniques. Their selection of materials, in particular, showed their keen understanding of the plot’s physical environment, as well as the social-cultural characteristics and idiosyncrasies of the people who would dwell in the house. Not surprisingly, most submittals demonstrated solid examples of the architects’ understanding of the uniqueness of the given challenge.

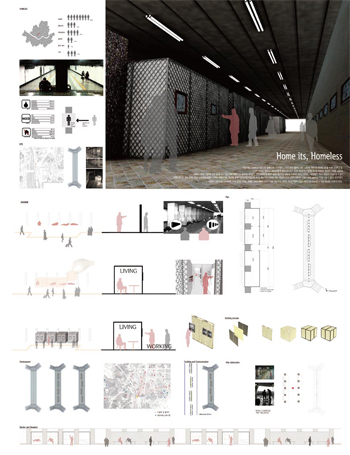

Some entries, however, lacked in detail and execution, despite the incredible ideas they embodied. Others were the exact opposite. “Home its, Homeless,” is the project that I’d say most skillfully accommodated the theme of this year’s competition and is also the most concise and powerful piece. The students used in such austere, meaningful and beautiful manners the seemingly useless space that exists between crude columns inside the shabby underpass and created a dwelling out of it. They adopted common, easy-to-use recycled materials to construct their housing, thus seamlessly blending into the surrounding environment. Regrettably, their perspectiv showed a poor representation of the bedspring wire-the lack of consideration for details such as the splicing-and insufficient thinking and execution of corrugated cardboard installation, among other things.

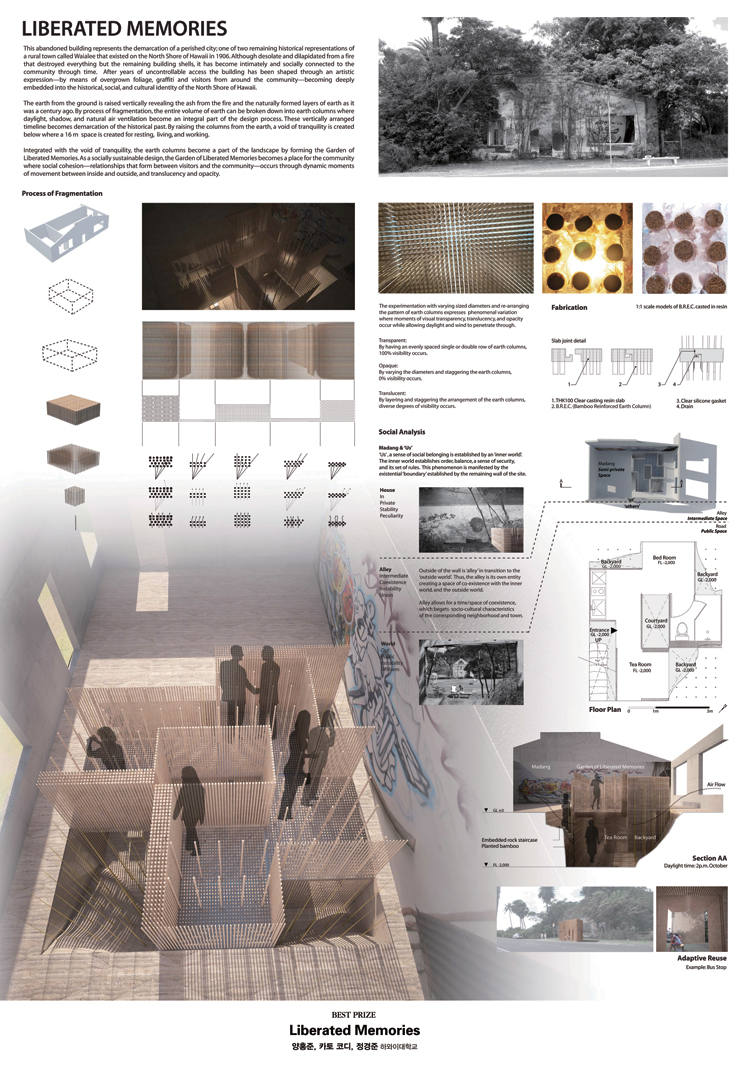

In contrast, “Liberated Memories” showcases a deserted school in Hawaii. The proposal had a high level of execution. The way the structure is connected to the underground passage and uncovers the 100-year-old history imbued in the physical space of the plot is particularly engaging and poetic. The students mainly used columns that were made of indigenous materials, such as bamboo and volcanic ash, and utilized them in such a way that their ideas were realized into practical experimentation and a concrete production. The way they took flooring, sun and the movement of residents into consideration while arranging the slim columns is diverse, exquisite and precise. And their execution through the light and movement is so beautiful that it closely resembles poetry. But do they represent the competition’s challenge of creating a dwelling with minimum costs and minimum intervention? Does their project embody architecture that is direct and essential? I’m sorry they didn’t win.

“I-Scale House” features an idea that is structurally consistent, in which designers used the easy-to-get, corrugated cardboards that were cut into specific dimensions and then put together like a mosaic rendering. The technique reinforced the structure, which turned out to be a simple dwelling with a cozy, warm feel to it, as implied in its title. The project also features a detailed plan, an elevation and a section scheme. Nevertheless, the execution on the cardboard (cutting and assembling) was somewhat irrational, unorganized and inconsistent.

“An Onggi House,” an energy-smart project, utilized the waste heat generated at Onggi (traditional Korean earthenware) furnaces. Cleverly enough, the team took advantage of the soil and broken Onggi pieces that can be found in the studios; they embodied in the final product their successful experimentation with color change and strength of the materials, after the baking process was completed. But the team lacked consideration for the proposed dimension of the house, which was to have four 2×2×2m cubes. Moreover, two of their cubes only had walls and floors. I found that rather presumptuous, and thus the house was excluded from the grand prize and supreme award categories.

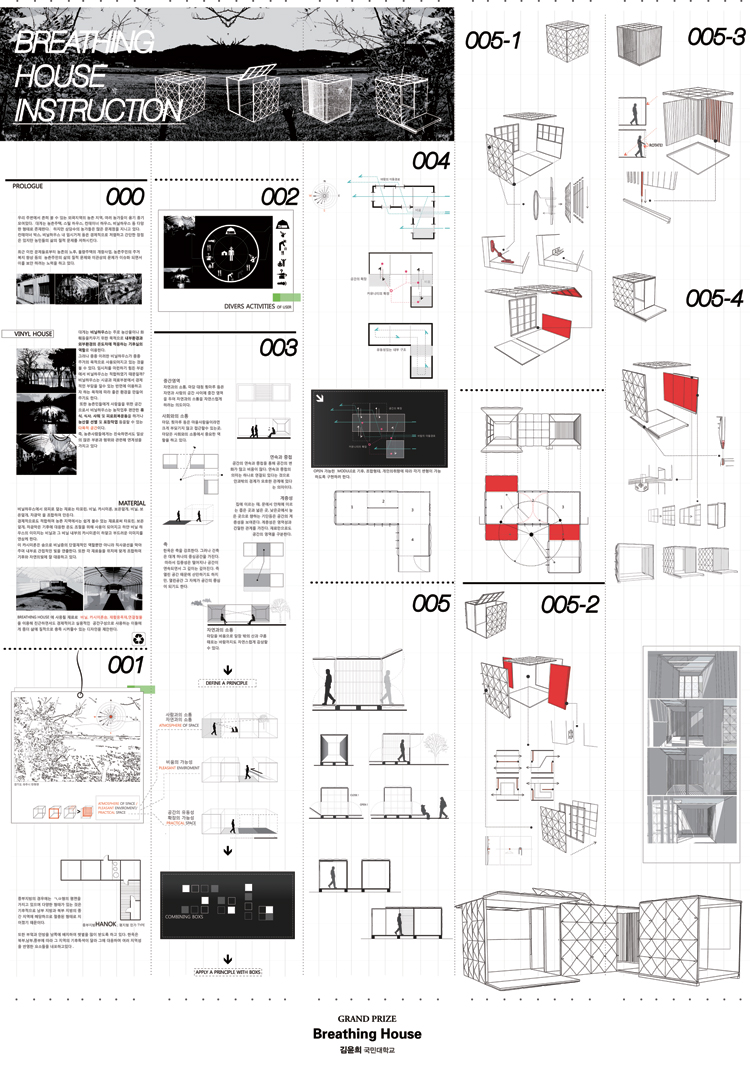

“Breathing House” has its roots in the housing problems found in rural farming communities across the country. The team used materials for vinyl greenhouses (that are commonly found in agricultural areas) as their main ingredients and showed full applicability for the competition’s minimum material, minimum intervention and minimum dismantling initiative. I particularly noted their simple, clear and realistic approaches to building. It is incredible the way they had come up with many combinations of assembling the four 2×2×2m cubes, which offers highly adaptable solutions to the elements such as sun and winds. The vinyl cover and the cotton-based insulation

material for the inside are not only effective in heating the house, but also in blocking out the sun, when necessary. Also, the austere plywood partitions and the louvers shutter that could adjust the level of ventilation, illumination and even privacy, are some of the finest features incorporated into the project. But the house raises the question of permanency and durability and lacks the planning for the bathroom and kitchen. It also lacks more practical experimentation, such as fabricating a mock-up to back up their idea. The weaknesses notwithstanding, “Breathing House” is a solid proposal, not only as a final outcome but also as a landmark that embodies the imperative of its existence in the social, cultural and physical context of the land on which it stands. The house has successfully materialized the architects’ inquiries on these issues and the answers they have obtained in a simple, concise form and shape.

As an architect who has been in the industry for quite some time, I once again emphasize the fact that good architecture is not all about “constructing”-with agendas and intentions. It is more about “making” with deep understanding, consideration, patience and experimenting and implementation.

Written by Cho Byoung-soo (Byoungsoo Cho Architects)

Subject Description

Investigation of Small Shelters

"I don’t believe in one absolute idea in architecture

but in thoughtful description and how it is executed."

- Byoungsoo Cho, Harvard University GSD lecture, April 2006

The goal of the 28th Space Prize for International Students in Architectural Design is to explore the possibilities in sustainable living and architecture. Thus a successful project entry would be one that clearly presents an innovative and experimental exploration in architecture and design, suggesting sustainability through minimal ways of living, minimal ways of building, minimal use of materials, minimal construction methods, and minimal ways of dismantling. The shelter ought to contribute positively to the site and surroundings while leaving the least impact upon removal. Great amount of reference and study can be found through historical artifacts and architecture from history to the 20th century modern period but everyday architecture and objects including local building and construction types should not be ignored. The successful project will contribute positively to the current state of Architecture to any local cultural context while also within the larger frame. The philosophical idea that supports this approach also could be found from ourhistorical and local contexts, to the avant-garde philosophy at the turn of the century as exemplified by such ideas as ‘pragmatism’ quoted below from the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Written by Cho Byoung-soo

Design Conditions

Size

- Shelter not to exceed 16m2 in floor area but may include additional circulation area of 1㎡. (ie: 4[four] 2x2x2m units)

- According to local cultural context or building traditions, shape or form of shelter may be altered w/ explanation

* may reference ’Soswaewon Rest Box’ from 2009 Gwangju Design Biennale also published in October 2009 issue of SPACE

Site

An existing physical site within your geographical context of your choice making use of land otherwise considered "less valuable," "left-over," or even disregarded (ie: a steep hillside, next to a highway, flood plain, etc.)

Materials

Should be kept to a minimum and to their standard "off-the-shelf" manufactured sizes when possible while exploring new, experimental and innovative design

Construction Method

Should be locally available and of neighboring resources while minimizing need for industrial machinery. (ie: manual labor, simple construction, hand made)

GRAND PRIZE

Kim Yun-hee

Kookmin University, Department of Architecture

Breathing House

Greenhouses made of vinyl and container boxes are two types of improvised residential homes most often found in the rural or farming areas of Korea. They are economical and easy to construct, so that they are viable options for farmers looking for a convenient living space. However, the problem is that these types of accommodations do not provide pleasant or durable living conditions.

Greenhouses made of vinyl and container boxes are two types of improvised residential homes most often found in the rural or farming areas of Korea. They are economical and easy to construct, so that they are viable options for farmers looking for a convenient living space. However, the problem is that these types of accommodations do not provide pleasant or durable living conditions.

Using better construction materials, it would be possible to provide these needy farmers with better living environments. The question is if this approach represents a sustainable option to resolve the housing problem and also to improve the overall living standards of the farmers in question. If this path is pursued, it could lead to more financial pressure on farmers. Besides, farmers might feel reluctant to accept the offer, as they would be identified as a lower earning class among farming households.

Due to these reasons, I gave a lot of thought to how to propose a sustainable housing type for farmers. Then I started paying attention to vinyl greenhouses. Vinyl greenhouses are very attractive and have a lot of inherent possibilities. Using a simple and strong structure and form, the purity of the white color found in the cashmere cotton inside and the texture of the vinyl that covers the exterior change depending on time, angle and season.

Vinyl greenhouses are made of a combination of vinyl, cashmere, heating covers, sunlight block film and a tarpaulin, etc. Each material is used to deal with the changing climate. A vinyl greenhouse is the most economical way to create a greenhouse effect, trapping the warm air inside during winter and opening to the cool breeze during summer.

The cashmere cotton inside functions not only as insulation, but also as a way to disperse indirect light between fibers. Here, I would like to propose a small house by suggesting a movable module that uses materials that are easy to collect, with excellent properties, highlighting the advantages of a vinyl greenhouse. I call this a breathing house. The floor composition method of Korean-style homes is applied as a space structure. Korean-style homes have a structure and functionality that can cope with the climate present in different regions: They are well ventilated, well lighted and also can cope with the distinct changes in weather.

The front yards, halls and narrow wooden porches enable communication between nature and humans. There are a lot of resulting changes and emptiness by continuing and overlapping space—this connects with nature by obscuring the boundary of the indoor and outdoor areas.

Based on the basics of a Korean-style house, the breathing house is composed of modules that can express the dynamic flow in space and the possibility to expand as void space or space for communication with nature. Each module of a breathing house enables it to open and close freely. The open face absorbs wind as it flows in, which expands the space inside. A part of the wall that can be opened and lifted blocks the strong sunlight. The outer cover lets indirect light into the house.

Additionally, the fourth module is connected to the outdoors, exposing the floor after the outer cover is removed. This kind of space structure is meant to correspond to individual options and climate preferences. A breathing house is a small option meant to improve the living standards of farmers without changing their current living style.

PRIZE OF EXCELLENCE

Yang Hong-joon, Kody Kato, Chung Kyung-joon

University of Hawai‘i at Manoa, School of Architecture

Liberated Memories

The Historical Axis _ A 6m road now severs the physical connection between the two surviving school buildings. In 2010, a historical axis will be manifested to redefine the relationship between the two. Traces of the past in the demolished interior walls, overgrown foliage, and graffiti by unknown visitors depict solitude and desolation.

The Historical Axis _ A 6m road now severs the physical connection between the two surviving school buildings. In 2010, a historical axis will be manifested to redefine the relationship between the two. Traces of the past in the demolished interior walls, overgrown foliage, and graffiti by unknown visitors depict solitude and desolation.

The Sensory Mediator: Earth Column _ Integration of the artifacts on the historical axis and a new program creates an experiential intervention that fuses architecture, landscape and sculpture. Our scheme’s central idea is to respond to the sense of place by embodying historical and social context via the layers of earth and ash from the fire that has settled over time. These layers of time serve as the architectural device in awakening the memories of Waialee town. By process of fragmentation, the earth embodying these layers will be fragmented to form earth columns. Daylight, shadow and wind are instrumental landscape features to the earth columns, which materialize the form of the Garden of Liberated Memories.

Pragmatic Programs for the Multi-dimensional Sense of Place _ This dynamic design was developed through two simultaneous experiments: utilizing the advantages of digital architecture, via scripting and programming, where various diameter sizes and arrangement of the earth columns were optimized; at the same time, physical experimentation was conducted with bamboo, earth and resin to relate their materiality to the program. The integration of earth, bamboo and resin formed an intricate correlation between structure, light and transparency. Resin slab is a mediator of light that creates an ambience of familiarity during the day, and emits tranquil, yet grandiose light that emphasizes its identity and a sense of place. The identity of the Garden of Liberated Memories correlates with the presence of the historical axis, and informs of the significance of each of these elements. The Garden of Liberated Memories presents a synergetic relationship with its site, creates a cultural artifact that increases awareness of history and blends light and materiality into the multi-dimensional experiences of the senses.

SPECIAL PRIZE

Song Kyung-ha, Song Young-jung, Lee Kwang-uk

Hongik University, School of Architecture

An Onggi House

I first came upon the idea of “earth” when I heard the main theme of the competition was to build an architecture integrated well with nature. Then I thought of ceramics made of clay, especially the Onggi (甕器, Korean traditional earthenware), with its superb ability to circulate the air and return it to the nature. The idea of living in a large, Onggi-shaped house seems a good one, given that the house has versatile functions, such as waterproofing and good air circulation.

I first came upon the idea of “earth” when I heard the main theme of the competition was to build an architecture integrated well with nature. Then I thought of ceramics made of clay, especially the Onggi (甕器, Korean traditional earthenware), with its superb ability to circulate the air and return it to the nature. The idea of living in a large, Onggi-shaped house seems a good one, given that the house has versatile functions, such as waterproofing and good air circulation.

One day, I visited a traditional kiln. Materials could be found everywhere in the village; these include clay, soil bricks, stones, wood and piles of broken porcelain pieces. Among the various materials, it was the broken porcelain pieces that drew my attention. Those piles stacked in the corner made me think of persistent craftsmanship in pursuit of perfection, and the familiar look of the broken pieces of Onggi returning to the earth left a strong impression within me.

My interest was also caught by the intense heat coming from a traditional kiln used to bake pottery for five days a month. The kiln, situated on a slope evenly distributes the heat starting at the bottom and working its way to the top-this process utilizes a tremendous amount of heat in an amazingly simple fashion.

By using these perceptions and ideas, I decided to make a small Jjimjilbang (heated resting room) for craftsmen. After blending crushed pieces of Onggi with clay, I baked them in a kiln to construct a room with a heated floor. Next, I completed a hot tub by burying an Onggi in the ground: a cool room where light and air move around freely, with smoke-blinding walls. Now, radiant heat is continuously streaming from the floor and walls, and water contained in the Onggi gets warm during the five days when the kiln is fired. The building is a resting place for the Onggi craftsmen who work 24-hour shifts; it is also a communal space for local residents.

There will still be a number of craftsmen who will laboriously accomplish their tasks and will patiently preserve their craftsmanship. I want to offer this house in honor of those craftsmen.

Park Jin-min, Choi Eun-jin, Choi Woon-ju

Korea University, Department of Architecture

I-scale house

What about ‘I-scale’? A scale is a measurement, an appropriate proportion that helps to understand or use an object. ‘I-scale house’ is a house that can be used appropriately by me, best representing my life.

What about ‘I-scale’? A scale is a measurement, an appropriate proportion that helps to understand or use an object. ‘I-scale house’ is a house that can be used appropriately by me, best representing my life.

The material used for this house is paper. Paper is a familiar and easy-to-handle material. I used pieces of wrapping paper that are normally thrown away after being used once. When paper is cut into small pieces and those small pieces are overlapped together, paper acquires its own rigidity. Additionally, when small pieces of paper are tied together through small holes on each piece, paper can be an excellent material to build a house. I made a frame by tying long pieces of paper together and then intersecting small and easy-to-use pieces of paper inside the frame. Then, I was able to create a frame large enough to build a 2×2m surface.

After a frame necessary to make one surface was completed, I prepared some connecting materials to tie one surface with another at a right angle, as well as in parallel. Then, I was able to build walls and a roof by stuffing the frame with the filling materials and connecting each surface. Paper was the only material used for the frame, as well as for the connecting and filling materials. The materials were again tied together through small holes. Furniture was created by the paper materials inserted inward from the frame. The different ways to insert filling materials generate the different façades of a structure.

A house is a place where life begins and slowly comes to completion. I thought that the memories of life were formed by the consecutive experiences of space, not by the visual symbols on a flat surface or façade. Even a small object is highly regarded in a small house.

Space is divided not by walls, but by objects featuring different functions. Thus, it was important to create the objects to express the space of this house. Each object was portrayed exactly as it was seen by its user.

Demolishing a house can be quite noisy and stressful, but demolishing this house can be a farewell party for me and my neighbors: The house will return to the original state of paper. When a house that was once filled with life disappears, the relationships and memories with the neighbors remain behind.

Kim Sung-yup, Kim Ji-young, Choi Soon-hyuck

Korea University, Department of Architecture

Home its, Homeless

The number of homeless in Korea is decreasing, but their continued presence is still recognized as one of the most important social problems here. There are many possibilities to address this problem. Based on a questionnaire sent to 100 homeless people, the respondents indicated that they desperately wanted to resolve the problems associated with hunger and shelter during the cold weather season, and also wanted to get back into society, asking that proper job training was made available to them. We believe that the existing methods for stamping out homelessness are not perfect. In particular, we believe that it is necessary to change the people’s bias regarding the homeless people’s issues and condition.

The number of homeless in Korea is decreasing, but their continued presence is still recognized as one of the most important social problems here. There are many possibilities to address this problem. Based on a questionnaire sent to 100 homeless people, the respondents indicated that they desperately wanted to resolve the problems associated with hunger and shelter during the cold weather season, and also wanted to get back into society, asking that proper job training was made available to them. We believe that the existing methods for stamping out homelessness are not perfect. In particular, we believe that it is necessary to change the people’s bias regarding the homeless people’s issues and condition.

Space between columns _ The distance between columns in the underground passage is 1.8m, which seems to make for a very small space compared with the size of the underground passage. If seen lengthwise, the columns line up looking like a wall, so the passers-by do not walk between columns. Many homeless people often gather in small spaces, where people do not frequently go by. It is an appropriate size for the homeless to lie down. However, as more homeless people move in these areas near columns, people prefer not to get too close to these spaces that let the traffic flow change.

Providing shelter _ Providing shelter to the homeless reduces the size of the slums that are mainly occupied by homeless people. This also enhances the living standards in those spaces. It is possible to restore the modified passer-by traffic flow, eliminating any obstacles. Inflow into society _ After restoring the traffic flow, I thought about how to enable positive communication between the homeless and the society. A group of people from smallsized ateliers, galleries, as well as art students, joined in a project to upgrade the entire underground passage near Seoul Station into a vibrant cultural exhibit space; later, we had a number of open discussions with other artists on the theme of the exhibit, which helped eliminate some of the bias against homeless by enabling better communication between them and the society. This addressed the three above-mentioned problems: proving shelter to the homeless, upgrading the slums in underground passages and helping the homeless get on their feet and back into society.

HONORABLE MENTION

Seo Dong-geon, Moon Ji-young, Kim Hong-seok

Pukyung National University, Department of Architecture

The Oldest but Latest Story about Housing

Lim Seong-hwan, Yu Ji-eun

Wonkwang University, Division of Architecture

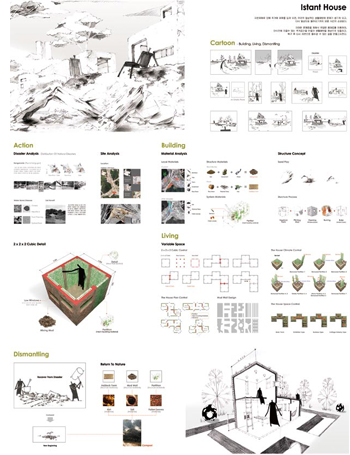

Instant House

Park Jeong-uk, Park Jin-kyu

Inha University, Department of Architecture

Dismantling Derelict Space

Sun Jin-woo, Park Go-eun

University of Seoul, Department of Architecture

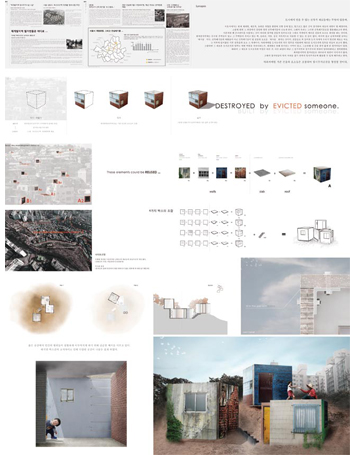

Destroyed by Evicted Someone

Si Deok-jin, Oh Jae-hoon

Kookmin University,

Korea University, Department of Architectur

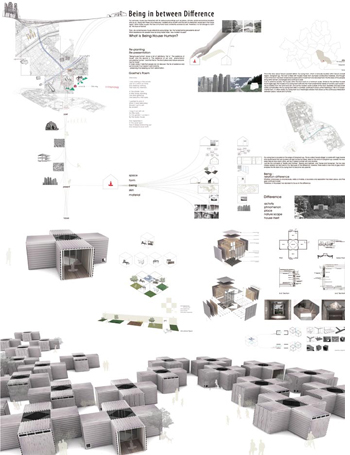

Being in between Difference